- Rsync Remote Directory Download

- Rsync Remote Directory

- Rsync Remote Directory With Spaces

- Rsync Remote Directory To Local

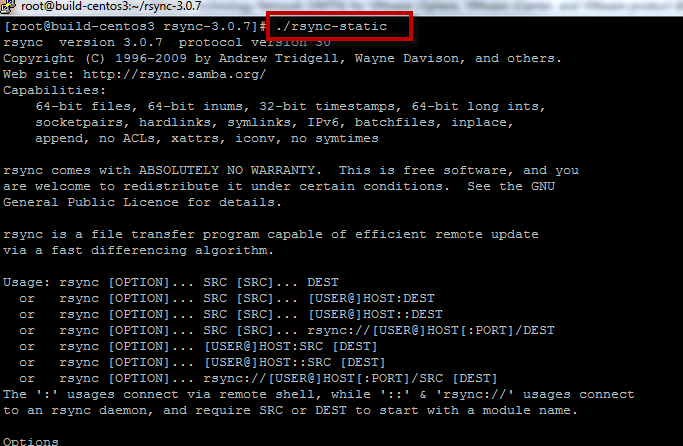

The rsync utility can backup files, synchronize directory trees, and much much more, both on the local machine and between two different hosts—via push and pull. Here is how to tame it.

This article explains:

Comment and share: How to back up a local Linux directory to a remote Linux host with rsync By Jack Wallen Jack Wallen is an award-winning writer for TechRepublic, The New Stack, and Linux New Media. One trick to do it is to use the -rsync-path parameter with the following value:-rsync-path='mkdir -p /tmp/fol1 && rsync' With -rsync-path you can specify what program is going to be used to start rsync in the remote machine and is run with the help of a shell.

- how to synchronize the contents of two local directories

- how to perform a secure rsync via ssh:

- an rsync push from the local host to a remote host

- an rsync pull from a remote host to the local host.

It goes without saying that rsync can have disastrous consequences if performed incorrectly, so whenever in doubt, initiate a –dry-run and always think before you type.

rsync for starters: synchronizing the contents of two local directories

To synchronize the contents of two directories on your local machine, use the rsync utility like this:

The trailing slash / ensures that the contents of your source-directory would transfer to the destination-directory (in this case) on the same host.

Without the trailing slash, your source-directory would become a sub directory of your destination-directory (in this case, both on the same host).

The -r option sets the recursive mode. It tells rsync to traverse subdirectories.

Remote rsync via ssh

Synchronizing local directories using rsync is a piece of cake, but what if you want to securely rsync files and directories between two separate hosts using ssh with public key authentication over the network? Easy.

There are two ways to accomplish this:

- a push operation transfers data from the local host to the remote host,

and the other way around:

- a pull operation transfers data from the remote host to the local host.

rsync push: transfer data from your local host to a remote host

To initiate an rsync push from the local host to a remote host (or from one remote host to another) via ssh, you can use this command at the prompt of the host that will push its data:

rsync pull: transfer data from a remote host to your local host

To initiate an rsync pull from a remote host to the local host, you need to set up ssh with the private key placed locally (preferably in $HOME/.ssh of the active local user) and the corresponding public key located on the remote computer (in a separate line inside the file authorized_keys in in $HOME/.ssh of the remote user).

To set up the keys, follow steps 1 through 5 in this tutorial: How to Set Up a Connection between Two Hosts Using Authentication Based on Key Pairs for Remote Access via ssh, rsync.

Once you have verified that you can establish an ssh connection, you can now use this command:

The -p flag specifies the ssh port number on the remote host to connect to, so if your remote ssh demon listens on a different port number, you need to replace the default 22 with that port number. The parent directory on the target machine (in the above example DESTINATION) must already exist. OBJECT can be several files or directories (several, when using wildcards).

User mapping in rsync

rsync version 3.1.0 introduced user mapping with the –usermap and –groupmap options. This allows you to specify ownership of files on the remote system like this:

Since option -a will cause rsync to preserve ownership, you may want to puzzle its functionality together by setting individual flags (see above section about useful rsync options).

rsync in the cloud with systems that don't support root login

Many AMIs (Amazon Machine images) on AWS are configured in a way that disallows remote authentication as root (even though they may contain a public key in root's authorized_keys file). The administrator connects as an unauthorized user, then enters sudo su or sudo -i to acquire root privileges. This may be a good practice, but it's counterproductive when you want to use rsync. The utility may not be able to write to a directory owned by root:root unless root initiates the connection. So what's the fix?

The simplest way to work around the problem is by activating root login in

by using the parameter PermitRootLogin.

This parameter can take one of four values:

- PermitRootLogin without-password: this disables password authentication for root, allowing other authentication methods (such as keys);

- PermitRootLogin forced-commands-only: this allows root login with public key authentication, but only if the ‘command' option has been specified; no other authentication methods are allowed;

- PermitRootLogin no: this setting prohibits login as root regardless of the authentication method used;

- PermitRootLogin yes: allows unsafe login as root (you don't want this one).

- how to synchronize the contents of two local directories

- how to perform a secure rsync via ssh:

- an rsync push from the local host to a remote host

- an rsync pull from a remote host to the local host.

It goes without saying that rsync can have disastrous consequences if performed incorrectly, so whenever in doubt, initiate a –dry-run and always think before you type.

rsync for starters: synchronizing the contents of two local directories

To synchronize the contents of two directories on your local machine, use the rsync utility like this:

The trailing slash / ensures that the contents of your source-directory would transfer to the destination-directory (in this case) on the same host.

Without the trailing slash, your source-directory would become a sub directory of your destination-directory (in this case, both on the same host).

The -r option sets the recursive mode. It tells rsync to traverse subdirectories.

Remote rsync via ssh

Synchronizing local directories using rsync is a piece of cake, but what if you want to securely rsync files and directories between two separate hosts using ssh with public key authentication over the network? Easy.

There are two ways to accomplish this:

- a push operation transfers data from the local host to the remote host,

and the other way around:

- a pull operation transfers data from the remote host to the local host.

rsync push: transfer data from your local host to a remote host

To initiate an rsync push from the local host to a remote host (or from one remote host to another) via ssh, you can use this command at the prompt of the host that will push its data:

rsync pull: transfer data from a remote host to your local host

To initiate an rsync pull from a remote host to the local host, you need to set up ssh with the private key placed locally (preferably in $HOME/.ssh of the active local user) and the corresponding public key located on the remote computer (in a separate line inside the file authorized_keys in in $HOME/.ssh of the remote user).

To set up the keys, follow steps 1 through 5 in this tutorial: How to Set Up a Connection between Two Hosts Using Authentication Based on Key Pairs for Remote Access via ssh, rsync.

Once you have verified that you can establish an ssh connection, you can now use this command:

The -p flag specifies the ssh port number on the remote host to connect to, so if your remote ssh demon listens on a different port number, you need to replace the default 22 with that port number. The parent directory on the target machine (in the above example DESTINATION) must already exist. OBJECT can be several files or directories (several, when using wildcards).

User mapping in rsync

rsync version 3.1.0 introduced user mapping with the –usermap and –groupmap options. This allows you to specify ownership of files on the remote system like this:

Since option -a will cause rsync to preserve ownership, you may want to puzzle its functionality together by setting individual flags (see above section about useful rsync options).

rsync in the cloud with systems that don't support root login

Many AMIs (Amazon Machine images) on AWS are configured in a way that disallows remote authentication as root (even though they may contain a public key in root's authorized_keys file). The administrator connects as an unauthorized user, then enters sudo su or sudo -i to acquire root privileges. This may be a good practice, but it's counterproductive when you want to use rsync. The utility may not be able to write to a directory owned by root:root unless root initiates the connection. So what's the fix?

The simplest way to work around the problem is by activating root login in

by using the parameter PermitRootLogin.

This parameter can take one of four values:

- PermitRootLogin without-password: this disables password authentication for root, allowing other authentication methods (such as keys);

- PermitRootLogin forced-commands-only: this allows root login with public key authentication, but only if the ‘command' option has been specified; no other authentication methods are allowed;

- PermitRootLogin no: this setting prohibits login as root regardless of the authentication method used;

- PermitRootLogin yes: allows unsafe login as root (you don't want this one).

Set this option as follows:

and append your public key into the authorized_keys file that is located in the $HOME/.ssh folder that belongs to root. For more details on how to create and install your key pairs read How to Set Up a SSH Connection Using Authentication Based on Key Pairs.

With PermitRootLogin without-password in place, SSH will still ask the root user for a password, even though no password will work. This behavior is rather unnerving (security by obscurity?). To suppress this behavior, add these two lines to /etc/ssh/sshd_config:

If you would like to prohibit password authentication for all users on the system, this will do the trick:

Useful rsync options

Some useful rsync options include:

- a or –archive: activates the archive mode; this mode tells rsync to:

- traverse directories recursively (implies option -r),

- preserve:

- symbolic links (-l or –links) and

- other special and device files (-D or –devices and –specials); with additional options for restricions on link validity and the like,

- transfer:

- permissions (implied option -p or –perms),

- user and group ownerships (-o for –owner and -g for –group), and

- timestamps (-t or –times),

- but does not imply the -H option for hard links (this option can be set separately);

- e specifies the remote shell to use (see section on rsync via ssh);

- h or –human-readable: outputs file sizes in a human-readable format with units of K for kilobytes, M for megabytes, and G for gigabytes; if specified twice (-hh), the units are powers of 1024 instead of the default 1000;

- z or –compress enables compression;

- –progress outputs a line-by-line activity report (implies -v for –verbose, an option that in itself can be very useful when troubleshooting connection problems);

- R replicates the complete directory tree with an absolute path instead of a relative one (/the/complete/original/path/to/object becomes /destination/path/the/complete/original/path/to/object);

- n or –dry-run allows for a risk-free test run of rsync without actually copying anything; remember to ask for verbose output using either -v, –verboseor –progress.

rsync supports plenty of other useful options that make for rather sophisticated methods of operation. For additional inspiration, you can always refer to the manual:

Admins (or normal users) often need to back up files or keep them in sync between multiple places (including local and remote) without transferring and overwrite all files on the target every time. One of the most useful tools in a sysadmin's belt for this kind of task is rsync.

The rsync tool can recursively navigate a directory structure and update a second location with any new/changed/removed files. It checks to see if files exist in the destination before sending them, saving bandwidth and time for everything it skips. Also, rsync provides the ability to synchronize a directory structure (or even a single file) with another destination, local or remote. To accomplish this efficiently, by default, it will check the modification times of files. It can also do a quick hash check of files on the source and destination to determine whether or not it needs to transfer a new copy, possibly saving significant time and bandwidth.

[ You might also like: 5 advanced rsync tips for Linux sysadmins ]

Since it comes packaged with most Linux distributions by default, it should be easy to get started. This is also the case with macOS, *BSDs, and other Unix-like operating systems. Working with rsync is easy and can be used on the command line, in scripts, and some tools wrap it in a nice UI for managing tasks.

More Linux resources

On the command line, rsync is generally invoked using a handful of parameters to define how it should behave since it's a flexible tool. In its simplest form, rsync can be told to ensure that a file in one location should be the same in a second location in a filesystem.

Example:

It's ordinarily desirable to pass rsync a few parameters to ensure things behave the way a human would expect them to. Passing parameters such as -a for 'archive' is quite common as it is a 'meta-parameter' that automatically invokes a handful of others for you. The -a is equivalent to -rlptgoD, which breaks down to:

-r: Recurse through directories (as opposed to only working on files in the current directory)-l: Copy symlinks as new symlinks-p: Preserve permissions-t: Preserve modification times-g: Preserve group ownership-o: Preserve user ownership (which is restricted to only superusers when dealing with other user's files)-D: Copy device files

Rsync Remote Directory Download

Often this works how the user wants and no significant changes are necessary. But, some of those might be contrary to what a user needs, so breaking it out into the specific functionality might be the right answer.

Rsync Remote Directory

Other noteworthy options include:

-n: Dry run the command without transferring files--list-only: Only show the list of files thatrsyncwould transfer-P: Show progress per file-v: Show progress overall, outputting information about each file as it completes it-u: Skip updating target files if they are newer than the source-q: Quiet mode. Useful for inclusion in scripting when the terminal output is not required-c: Use a checksum value to determine which files to skip, rather than the modification time and size--existing: Only update files, but don't create new ones that are missing--files-from=FILE: Read list source files from a text file--exclude=PATTERN: Use PATTERN to exclude files from the sync--exclude-from=FILE: Same as above, but read from a file--include=PATTERN: Also used to negate the exclusion rules--include-from=FILE: Same as above, but read from a file

My personal default set of parameters for rsync end up being -avuP (archive, verbose output, update only new files, and show the progress of the work being done).

Rsync Remote Directory With Spaces

Source and targets

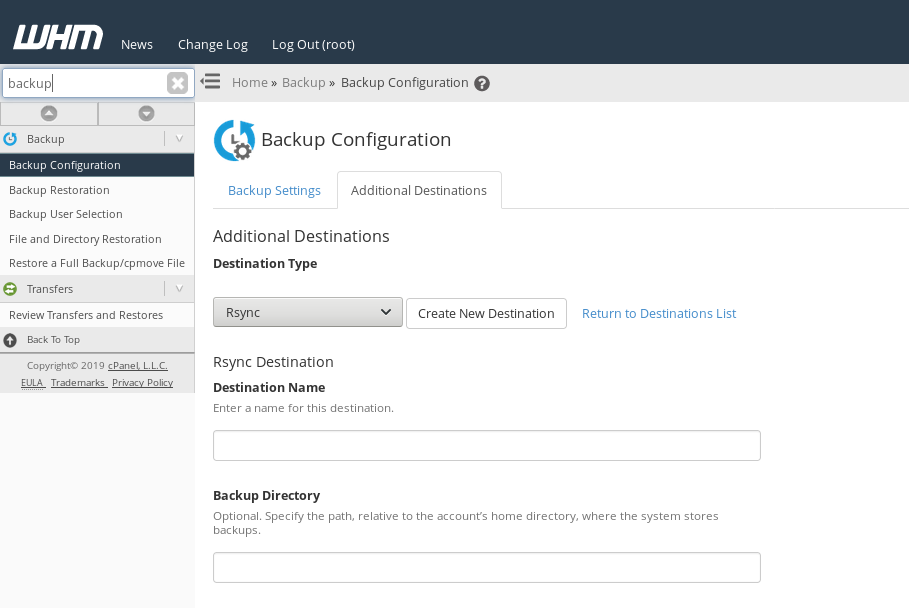

The source and target for the sync are files and directories. Also, rsync provides the functionality to interact with remote systems over SSH, which keeps the user from needing to set up network shares to be able to sync files from one place to another. This means you can easily script rsync jobs after configuring SSH keys on both ends, removing the need to manually login in for remote file sync.

Rsync Remote Directory To Local

Example: